When I first designed my fundraising workshop, I spent six months turning my intuitions, patterns, and experiences into a system that could be taught. The work was about making implicit knowledge explicit and figuring out how to make it land for other people.

While I’m mostly known as a fundraiser, a significant portion of my career has been spent designing and running large-scale advocacy programs. Not from the point of view of policy positions or campaign tactics, but around power, identity, and form: what makes something real, what makes it feel serious, and what actually gets people to move. (Both fundraising and advocacy are about the perception of power, elegance, and possibility.)

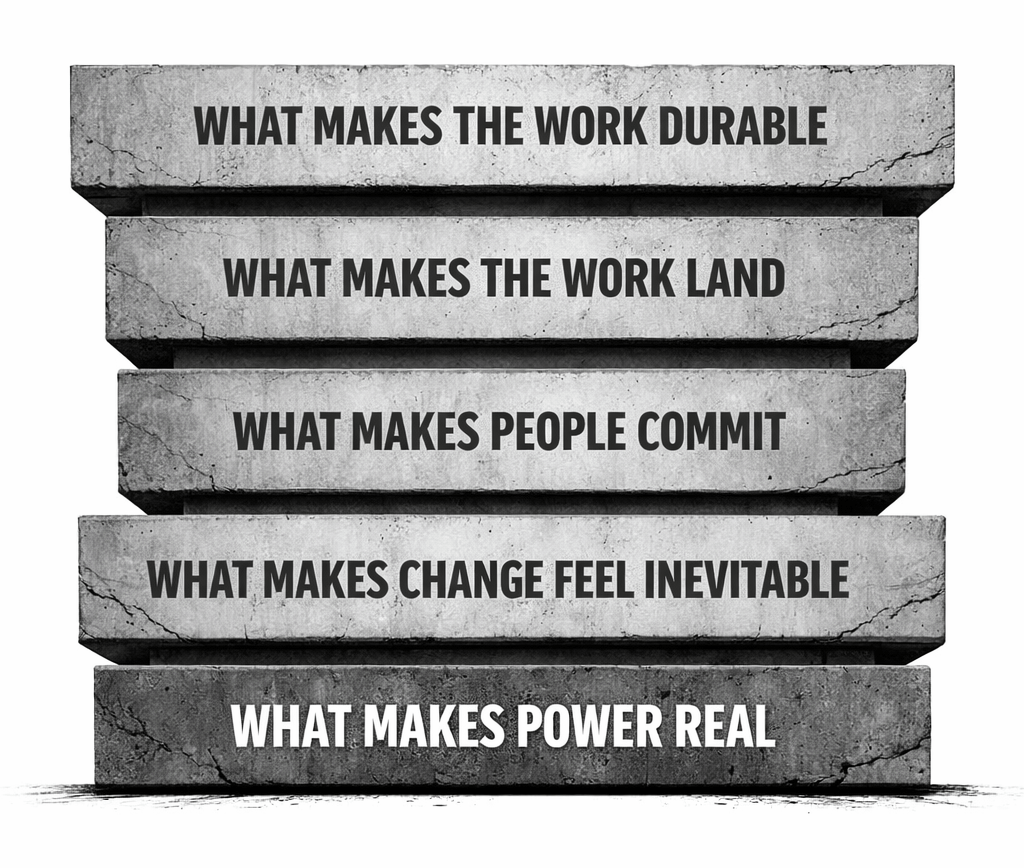

I’ve started the same synthesis work around my experience running advocacy programs. This document is an early attempt to lay out a set of design tenets for building advocacy efforts that have the potential to matter.

This is a 1.0. There will be revisions. But given the state of the world and conversations already underway, it felt more useful to put this into use than to wait for it to be finished.

Listen to this as a summary podcast from NotebookLLM:

1. What Makes Power Real

1.1 Real power derives from form.

- Power doesn’t come from belief, attention, or energy. It also doesn’t come from action, speed, or reach.

- It comes from how the system is built — what it allows, blocks, and channels.

- The structure determines what kind of power is possible, and where it lands.

1.2 Real power is intentional.

- Visibility, activity, and attention aren’t power unless they’re carried through structure.

- Loudness without alignment doesn’t move systems.

- Force comes from coordinated form — not how much energy you generate.

1.3 Real power carries consequence.

- You don’t get power without taking a risk. Someone has to be exposed — including you.

- Power means showing you’re willing to go further, carry more risk, and hold longer than the person you’re confronting.

- It only works if it creates real consequence — for the people inside the system and the ones it targets.

1.4 Real power is direct, not mediated.

- If your action depends on someone else to act for you, it’s not power — it’s a request.

- Asking leaders to fix it for you is not the same as forcing the fix.

- Power means changing something yourself — not demanding that someone else do it.

1.5 Real power is comprehensive, compounding, and constricting.

- A single tactic is a bet. Real power is built across fronts — in parallel, not in sequence.

- It gains strength over time by tightening, accelerating, and reducing options.

- If there’s an open lane, they’ll take it. Power means closing every escape route until there’s nowhere left to run.

2. What Makes Change Feel Inevitable

2.1 The actions should feel like a system.

- The parts don’t just coexist — they complete each other.

- It should read as a single, coordinated effort, not a pile of activity.

- They’re activating a system, not taking action.

2.2 Each piece should feel required.

- Every part should carry weight the others can’t.

- If one piece drops, the whole thing should feel unstable.

- This is how people recognize something as real — when nothing feels extra, and nothing feels safe to skip.

2.3 The strategy should feel complete.

- It shouldn’t feel like something’s missing — or like it’s still waiting to be finished.

- The completeness builds belief. People trust a shape that makes senses.

- People should look at it and say: “Right, this will work.”

2.4 The choices should feel deliberate.

- People should be able to see what was chosen — and what was left out.

- If everything is included, nothing feels serious.

- Sharp choices build trust in the structure. They signal: this wasn’t built by accident.

2.5 The structure should carry you into motion.

- The next step should feel obvious — not because it was assigned, but because it’s what the shape demands.

- The design should make action feel like the default — not a decision.

- When the form is strong, people don’t wait to be convinced. They move.

3. What Makes People Commit

3.1 People commit when the work redefines how they’re seen.

- The work has to offer people the chance to become more of who they already believe themselves to be.

- It should let them surface, express, and act from parts of their identity that usually stay quiet.

- It has to create space for transformation — a shift in how they see themselves and how they move through the world.

3.2 People commit when there’s something to join.

- The act isn’t just doing something — it’s joining a new formation that makes the action coherent.

- Joining gives structure and meaning to what would otherwise feel like a task, a favor, or a request.

- Without something to join, participation stays shallow — it doesn’t convert.

3.3 People commit when the ask is consequential.

- People recognize when the ask actually matters — when it carries weight.

- If it doesn’t impose cost, it doesn’t carry power.

- The ask should signal scale, seriousness, and consequence — or don’t make it.

3.4 People commit when they’re fully present and engaged.

- People step in when the work needs their thinking, their energy, and their creativity.

- Engagement isn’t a reward — it’s what turns attention into investment.

- If the structure doesn’t need them in full, they’ll stay partial.

3.5 People commit when they’re asked to take risk.

- People take the work seriously when it asks something serious of them.

- If there’s no cost to stepping in, there’s no commitment behind it.

- The risk doesn’t have to be extreme — but it has to be real.

4. What Makes the Work Land

4.1 It should be obvious that people with real capacity are behind the work.

- The work should not read as symbolic, aspirational, or exploratory.

- Who is behind it — and what they can actually do — should be apparent without explanation.

- The presence of real capacity changes how everything else is interpreted.

4.2 The form itself should look and feel consequential.

- Before anyone agrees with the politics, the work should feel real.

- The structure, scale, and posture should suggest that something tangible is at stake.

- If it looks lightweight, procedural, or safe, it won’t land as power.

4.3 It should feel like an escalation or reset — not a repetition.

- The work should register as a change in phase, not another turn of the same crank.

- Observers should sense that the terms have shifted.

- Novelty matters only insofar as it signals escalation, reset, or raised stakes.

4.4 The ask should force a real calculation.

- The way the ask is framed should make people stop and assess risk.

- Responding — or refusing — should clearly carry consequences.

- If the ask doesn’t trigger calculation, it doesn’t land as serious.

4.5 The work should make neutrality uncomfortable.

- The work lands when staying silent starts to feel exposed.

- People inside institutions begin to feel that doing nothing now says something about them.

- This is how pressure moves without formal authority or enforcement.

5. What Makes the Work Durable

5.1 The system should be ready when the moment arrives.

- When people show up ready to act, the structure has to already exist.

- You don’t get time to assemble something once the moment is here.

- If the system isn’t ready, people move on and the window closes.

5.2 The system should be able to dodge and weave.

- The target will shift. The terrain will change. The work has to adjust.

- Tactics need to change without losing the underlying direction.

- If the system can’t adapt under pressure, it fractures or stalls.

5.3 The system should offer a way in — not a full map.

- People don’t need the whole plan to begin.

- They need a first step that makes sense and feels grounded.

- If someone can’t see how to start, they won’t.

5.4 The structure should replace uncertainty with direction.

- The work should give people confidence they’re in the right place, doing the right thing.

- It should create calm by feeling intentional and well-considered.

- People don’t need certainty — they need to feel the system knows where it’s going.

5.5 The system should arc — not ladder.

- Change doesn’t move in neat steps. It moves in waves.

- The work needs room for escalation, recovery, and regrouping.

- Ladders turn commitment into process tasks; arcs let people stay in the work.

1 comment